[ad_1]

Chinook helicopters in Afghanistan.

The U.S. Army only has one type of heavy-lift helicopter. It is called the CH-47F Chinook, and it’s expected to remain in service until around 2060.

The service for years planned to upgrade Chinook into a Block II configuration with new rotors and other features so it could carry heavier payloads over longer distances.

The upgrades were needed so that the helicopter could lift heavy equipment in the kind of “high/hot” operating conditions the Army would likely face in Southeast Asia and the Persian Gulf.

It seemed like a sensible plan since so much lifting capacity had been lost with the addition of new equipment to protect the helicopter during the global war on terror.

However, midway through the Trump years, the Army suddenly revoked the priority designation it had conferred on the Chinook upgrade, and tried to cancel most of the program

It retained a requirement for 69 upgrades destined for Army special operators, because they were operating the oldest rotorcraft in the Army fleet.

But the 473 upgrades destined for the rest of the Army disappeared from plans.

Prime contractor Boeing

The Army assured Congress that it would work with Boeing to secure foreign sales in order to keep the plant running at a minimum sustaining rate of 18 Chinooks per year.

Two years later, that plan has not panned out.

Since the Army signaled its intention to walk away from the upgrade program, Boeing has not secured a single new international sale.

The company now says it can foresee a point in the near future when its production line will become “unsustainable.”

The company estimates that 18,000 jobs would be at risk—at least 2,000 at its plant in Ridley Township, Pennsylvania, and many thousands more across an industrial base of 280 suppliers.

Some of those suppliers are likely to go out of business entirely.

In addition to impacting the Chinook line, ending the upgrades would drive up the price of the only other aircraft built at the plant, the Marine Corps MV-22 Osprey, because that program would have to carry more of the plant’s overhead costs.

With the Osprey program itself approaching an inflection point as new production gives way to modifications of existing aircraft, the future of the Boeing rotorcraft complex is looking shaky.

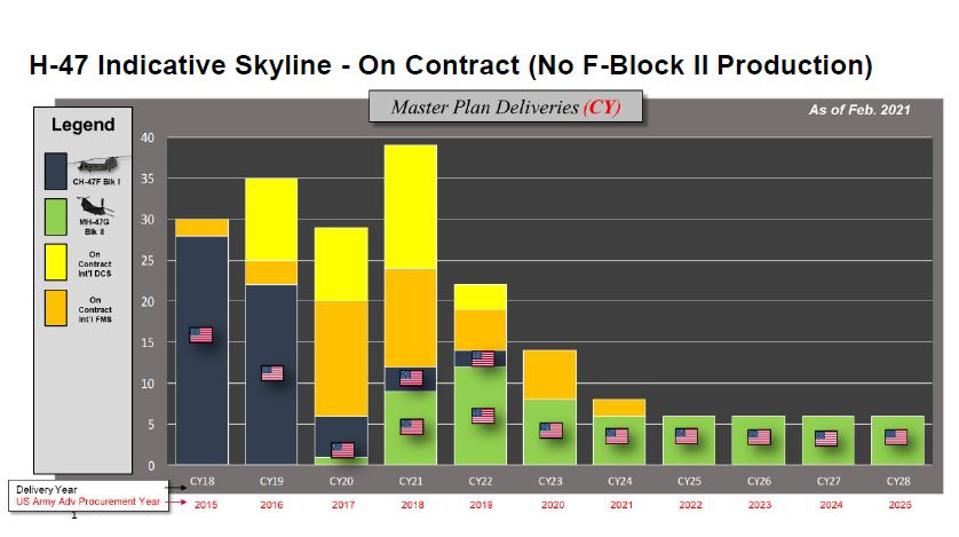

The following internal chart from Boeing (a contributor to my think tank) tells the tale.

Without Block II upgrades, production falls below a minimum sustaining rate.

In order to sustain its workforce and critical suppliers, the plant needs to assemble at least 18 aircraft per year. Without Block II upgrades, it is headed well below that level in 2023.

The local congressional delegation on both sides of the Delaware River—the plant sits right on the river—is not happy with the Army’s plan.

In fact, Congress added upgrade money to the Army’s Chinook request in the 2020 and 2021 budget cycles, and now looks poised to do the same in fiscal 2022.

This isn’t just about protecting local jobs.

Legislators are genuinely puzzled why the Army wants to defund a program to increase the lift of its heaviest helicopter even though the current version can’t lift the service’s Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (its next-generation jeep) or its light howitzers.

The Army’s current plan is reminiscent of the last time the plant was endangered, when defense secretary Dick Cheney sought to kill the Osprey tiltrotor during the early 1990s.

The local congressional delegation blocked that move too, and Osprey went on to transform the operations of both the Marine Corps and Air Force special operators—not to mention becoming one of the safest rotorcraft in the joint fleet.

So it seems that the Army is playing a losing hand in its efforts to kill Chinook upgrades. It has wasted political capital trying to deep-six a program enjoying broad political support in Congress, even though it lacks a backup plan for filling the gap in lift.

The closest I ever got to a rationale for not being able to lift the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle was when the chief of staff (himself a master aviator) told me two years ago the service didn’t plan to air-assault the vehicle in future conflicts.

Fair enough, but an old saw among strategists warns that no war plan long survives contact with the enemy. Why not at least have the option to lift critical equipment, even if that isn’t part of your plan?

The answer, presumably, is money. The Army has been starved of modernization funds for so long that it fears hobbling its most urgent projects unless it focuses funds there.

In the case of aviation, that means keeping the Future Vertical Lift program moving forward. However, the last two years have proven that both Future Vertical Lift and Chinook upgrades can be kept on track as long as Congress is supportive.

So why keep trying to kill a program that Congress wants to fund? That just increases the likelihood the money ends up coming from a place the Army finds unpalatable.

There’s another reason for the Army to reverse itself and support upgrades to Chinook.

Industrial policy is fast becoming a centerpiece of Biden economic strategy, so doing unnecessary damage to the biggest industrial complex in the Delaware Valley (a stone’s throw from the president’s home state, in a key swing state) is not going to win any friends at the White House.

Thus, for operational, economic and political reasons, the smartest move the Army could make at this point is to embrace Block II upgrades to the Chinook helicopter like a long lost friend.

[ad_2]