[ad_1]

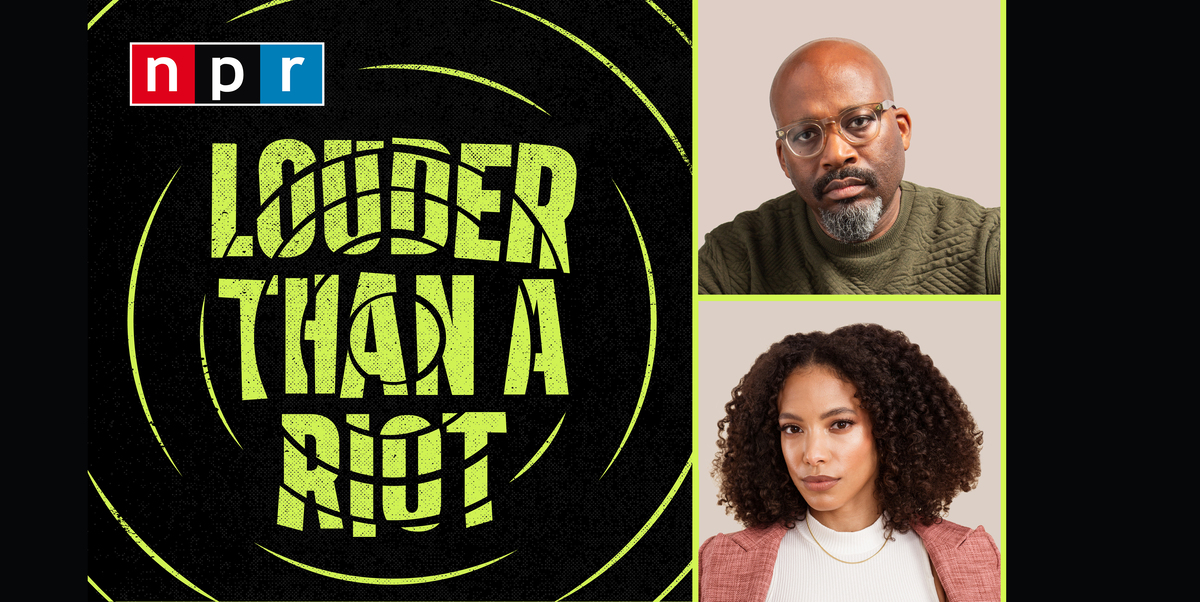

Rodney Carmichael and Sidney Madden of NPR’s new podcast “Louder Than A Riot”

Christian Cody and Joshua Kissi/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Christian Cody and Joshua Kissi/NPR

Rodney Carmichael and Sidney Madden of NPR’s new podcast “Louder Than A Riot”

Christian Cody and Joshua Kissi/NPR

By now, the story of hip hop’s ascent — from makeshift turn-up music slapped together by poor Black and Latino kids at a South Bronx party to the dominant musical idiom of young people around the world — is pretty well-known. But less attention has been paid to how hip-hop continues to be shaped by another American phenomenon: the explosion of the carceral state. That connection is what Sidney Madden and Rodney Carmichael, our colleagues and play-cousins at NPR Music, set out to answer on their brand new podcast, Louder Than a Riot. It’s a show about race, music, and criminal justice — and also the tale of a wild conspiracy theory.

This week, we’re running the pilot episode of their podcast in our feed. I sat down with Sidney and Rodney to ask them about why these connections fascinated them so much and what they learned. (Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.)

Over the last 40 years, the nation’s prison population has exploded and we’ve seen a ratcheting up of policing. Coincidentally, hip-hop was born in the late ’70s, so these two things were overlapping phenomena. So how has mass incarceration shaped hip-hop?

Rodney Carmichael: When you think about it from a pop culture standpoint, hip-hop was definitely before everything else in terms of commenting on and critiquing the criminal justice system and Black America’s relationship to it.

Sidney Madden: I love how you said two phenomena in America, because these are strictly American born-and-bred pieces of societal ethos. The thing that we’re trying to really spell out in our show is that these phenomena are not disparate. They intersect and intermingle a lot more than people think they do. As you said, hip-hop was being birthed in the late ’70s, with Kool Herc and Cindy Campbell and those back-to-school parties, laying the foundation and the blueprint of a counterculture moving to the center and becoming pop culture. That happened literally at the same time as America was constructing what we now know is the prison industrial complex. It was physically building more private prisons. It was also psychologically calcifying and certifying what a criminal in America is, and doing that by working off the building blocks of the legacy of slavery in this country.

So with all those things like marinating in the soup, there’s so much to debate and unpack about it. What does a rapper look like? What is considered political rap? Who is allowed to have a voice in hip-hop?

Imma quote the LOX here real quick: There’s so much about money, power and respect. There’s the money that flows in through the music industry, and corporations that profit off of the imagery in hip-hop, and then also money that flows through the prison industrial complex as we know it. Then, there’s the power of the oral tradition of hip-hop, and then also the powers that be that rob hip-hop of its agency. And then respect—or lack thereof—for the Black community that birthed America’s most dominant, consumed, tortured and profitable art form. And that lack of respect leads to things like criminalization of the culture, things like inflated prison populations, generational trauma, degradation of health standards and humanity of Black people in America. It goes on and on.

What made the two of you so interested in this intersection?

RC: Hip-hop media has been making this connection; going all the way back to the early 2000s, The Source magazine was doing “Hip-hop Behind Bars” issues. And now, we’ve heard so much about mass incarceration in this country and it being this huge civil rights issue—surprisingly, somehow even becoming a bipartisan issue. But it still always feels like it’s talked about in a way that doesn’t really talk about real people and the real impact on them. There’s a lot of statistics, and the problem sometimes feels so far removed from the people who are living through those problems.

Using hip-hop as a way to frame it, then, helps, because the music is coming out of the same communities that are being disproportionately impacted by this problem. Their music is the soundtrack of the planet, and I would ask myself, What percentage of the hip-hop listening population understands how much their favorite rappers are being impacted by this thing over here? Going all the way back to the mid to late ’90s, rap’s music-purchasing fanbase was majority-white. I just feel like it was a huge disconnect in terms of them understanding. It’s one thing to to to hear your favorite rapper, like Snoop Dogg in “Murder Was The Case,” or Nas in “One Love” talking about sending letters to his incarcerated homies. But it’s another to ask, Why is it that so many rappers are seemingly infatuated with this topic?

SM: I think so many people who casually listen to hip-hop have the luxury to divorce it from the reality it’s being inspired by. And a lot of what we’re doing in this show is taking big cases, or cases that have been trending topics, that might seem to an outside spectator to happen in a vacuum to a lot of these rappers. But we’re connecting it all to a larger socio-political umbrella, to really connect these dots for listeners and have them have them question and challenge themselves, and challenge the role of huge institutions in it.

Christian Cody and Joshua Kissi/NPR

Right. You mentioned Nas — who is famously comes from Queensbridge Houses, the single largest public housing project in the United States. The entire industry is based on the voices of these people who come from the most impoverished places in the United States.

SM: And that’s the thing — in every single decade and every single subgenre, hip-hop has been calling out this inequality and this disparity, way before any academic was. It lives in every manifestation of hip-hop, and I’m trying to draw a through line between all of them, whether you talk about Nas or Tribe, or someone who would be more traditionally fit in like that “lyrical miracle” part, or someone who who came from like the SoundCloud era, like Lil Uzi Vert.

Y’all have been working on this for a little over 18 months. What was the most surprising thing you found in your reporting?

RC: I’m not a criminal justice reporter by trade or training, you know. But just as a Black man in this country, I had a very good general understanding of, like, Man, stuff is unfair. But when you really get to start digging down into cases, you’re able to see how the systemic and structural inequality actually plays out, case by case. There’s prosecutors and the overwhelming power that they wield in this country. There’s plea deals, and just how huge of a phenomenon they are in determining the fate of people who oftentimes can’t afford to afford the kind of lawyering that keeps you out of having to take plea deals. There’s obviously probation and parole, and the bail system.

We didn’t intentionally go into this series saying that we’re going to pick a case or rapper’s story that’s going to expose this element of the criminal justice system. But as we reported on each one, we would quickly see, oh, okay, Bobby Shmurda’s case really deals a lot with RICO laws. We saw how these laws were created for Mafiosos and organized crime, and were then used on unorganized teenage gangs in places like Brooklyn. That was kind of the surprise — that our selection of certain cases would end up exposing different elements of the system in that way.

SM: And then in the latter episodes, we say, This is how we got here. Now, what’s next? And the power of that is really tied to the moment we’re living in, in 2020, and the amount of reckonings that are flowing through society. There’s going to be a lot of really earnest and complicated conversations about the realities of reforming the criminal justice system, where they fall short, and the actual alternatives to reform. We lay all this groundwork down, and we give platforms to all these cases. And I think coming out on the other side of that, it’s really important to acknowledge the possibilities of what could be.

As someone who learned so much along the way, I learned about what our nation, world and society could be if things were different. And I think taking a crash course in that has been really enlightening.

[ad_2]