[ad_1]

Video games have had us infiltrating Nazi bases for decades now, but Paradise Lost takes a decidedly more tempered approach than the all-guns blazing action of Wolfenstein or Sniper Elite. Its underground bunker setting is almost completely desolate from the outset of the story, so the closest you’ll ever come to having a rifle is when you’re having a rifle through filing cabinets for clues to determine exactly what fate befell its inhabitants. Yet while I explored the often disturbing depths of Paradise Lost’s Swastika-adorned subterranea with a sustained sense of morbid fascination, its frustratingly sparse approach to storytelling meant that my emotional investment in the plight of its characters remained permanently stranded on the surface.

In Paradise Lost’s alternate history setting, World War II continued through to 1960, allowing enough time for the Nazis to develop powerful atomic weapons in subterranean bunker facilities. Eventually, under pressure from the US and Soviets, the Nazis unleashed a nuclear holocaust and retreated underground, reducing the entire European continent to an uninhabitable wasteland. Paradise Lost’s story picks up twenty years later, when a 12-year-old Polish survivor named Szymon enters one of these bunkers in search of a mysterious man who knew his late mother, and I felt an immediate pull to find out exactly who or what was lurking below.

Third Reich Rapture

The eerie descent into Paradise Lost’s cavernous expanse initially gives the impression that you’re in for some kind of bunker-bound BioShock, and this feeling is reinforced when Szymon soon strikes up a two-way radio relationship with Ewa, who plays an Atlas-style role in helping Szymon navigate through each area while keeping her true motivations unclear. But there are no Splicers or Big Daddies to fight as you pick through the remains of Paradise Lost’s deserted dystopia, and for the most part your actions are fairly basic and limited to reading letters, listening to audio logs, and pulling levers to power up any dormant mechanisms that impede your path forward.

Outside of your interactions with Ewa, which are reasonably engaging but generally restricted to the intercom microphones you come upon every once in a while, you’re effectively left alone to try and piece together the narrative by scouring each office and hallway for as much information as you can. By far the most stimulating way to absorb a bit of the bunker’s backstory is the handful of times you get access to an archaic E-V-E computer terminal, which provides you with black box-style recordings of the last moments of activity in any given area. E-V-E is the AI that controls the bunker’s security and agricultural systems, among other things, and it’s oddly fascinating to watch a critical moment in this place’s history unfold on the terminal screen in a flurry of human-tracking heat maps and crisis management probability calculations.

Curiously, these memory sequences are interactive, giving you control over where troops are deployed during a conflict between the Nazis and members of the Poland Underground State, for example. These choices helped to keep me engaged in the E-V-E interactions and they do have slight implications for Szymon’s story, but I could never really understand exactly how I was able to manipulate events that had already taken place. I guess I must have missed that memo, and believe me when I say I read absolutely every memo I could get my hands on.

In fact I sought out and pored over every scrap of information I could find in Paradise Lost, and yet I still don’t feel like I ever knew enough about the individuals on either side of its central conflict to really care about its outcome. At one point Ewa insists that Szymon explores the cells where Polish women were held for heinous experiments in eugenics, in order to pay respect to their individual stories. But there’s only so much you can learn when the sole interactive object in one cell is a used up punch card and another has nothing but a half-finished crossword puzzle, leaving it hard to connect with their struggle.

Bunker down

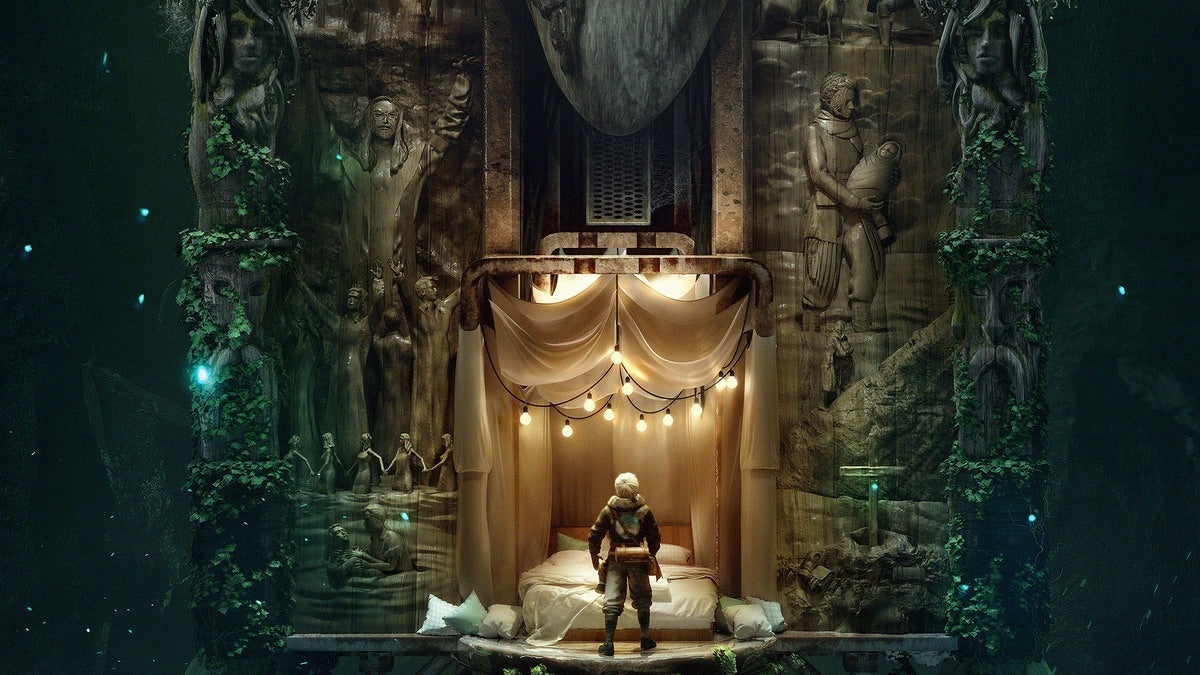

Such stingy storytelling is sadly consistent throughout Paradise Lost. Although the environments are extremely well crafted, from artificial beachsides beneath looming rock ceilings to the dishevelled dwellings of the living quarters, it’s mostly all look but don’t touch with very little available for up-close examination. Paradise Lost is like a bag of Doritos, it looks dense from the outside but once you actually open it up and reach around inside, it’s surprising just how much of the space is unused. It’s especially maddening just how often interactable drawers are completely empty when only one out of every ten or so can even be opened in the first place, particularly given the sluggish speed at which Szymon lumbers around each room in search of story morsels.

“

I was also frustrated by Paradise Lost’s tendency to deliberately prevent you from fully exploring its environments. Some of the larger areas have two paths you can take through them, but opting for one means permanently forgoing the other and any possible exposition it may be housing. Towards the story’s end you come upon three locked doors, each containing potentially vital clues, yet you’re only given the means to open two of them. Why do this? If the sole point of your game is to tell a story, why intentionally cordon off chunks of it from us? If it’s purely a decision to encourage repeat playthroughs, then it’s not one with much payoff – I played through Paradise Lost’s four-hour story a second time, choosing different paths and E-V-E choices the whole way through, and the only slightly altered outcome left me feeling equally indifferent.It certainly didn’t help that the intermittent nature of Szymon and Ewa’s radio chats meant I never bought into their bond, which becomes the primary focus towards the story’s climax. With their sparse conversations not providing enough substance to grab onto it all seemed a bit forced, and their fates just didn’t feel as important to me as Paradise Lost seemed to expect they would.

There were also some technical flaws present in the PC version that I played for review. Dialogue lines would often repeat, and on a couple of occasions I fell through the map, forcing a checkpoint restart. Since I opted to play with a controller with the Y-axis inverted for look controls, I was disappointed to find that it also reversed my inputs when I was interacting with objects – meaning I had to counterintuitively push the thumbstick forward to pull down on a lever, or pull it back to push through a door. That’s not how inverted camera controls should work.

[ad_2]