[ad_1]

Every family has that one story that gets passed around the dinner table when company is over. Maybe it’s how a couple met, or a chance run-in with a beloved celebrity. For my family the chosen lore was the time my dad’s adopted mother, Cleo, met his birth parents.

The story goes that Cleo was working as a nurse in an emergency room in Salt Lake City when a young American Indian couple came in with a beautiful baby boy.

The man was tall and lanky with a big belt buckle – it had hunks of turquoise in it and was too big for his frame. His partner was short and more round, and in her arms was a newborn.

The couple told Cleo they loved the baby very much, but couldn’t keep him. They were the first from their tribes to go to college and they couldn’t afford a child. She gave them the name of her priest to help them figure things out.

They were just one passing couple in a long shift at work. She didn’t think much of it until a few weeks later. She got a call from the same priest saying her prayers had been answered and he had a baby boy for her to adopt.

Bear Carrillo stands in front of his mother’s church, Our Lady of Guadelupe in Salt Lake City.

Jess Kung/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jess Kung/NPR

Bear Carrillo stands in front of his mother’s church, Our Lady of Guadelupe in Salt Lake City.

Jess Kung/NPR

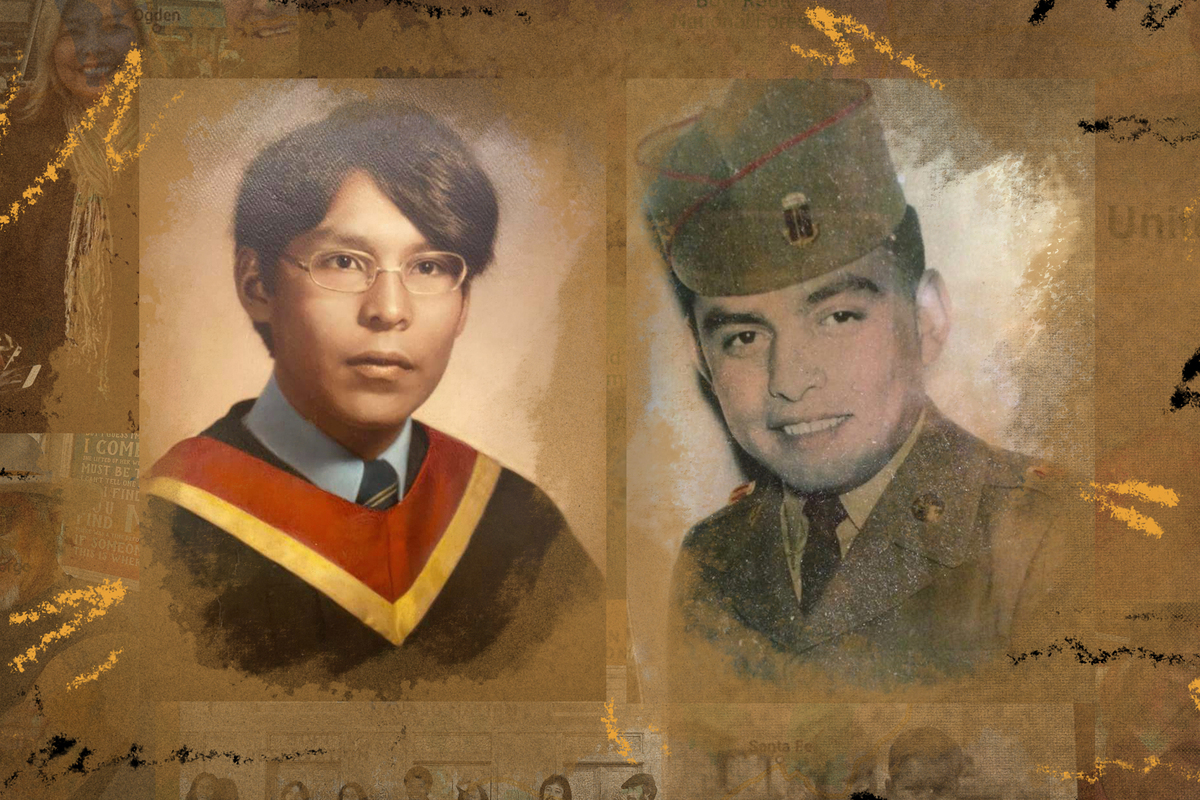

When my dad got older and started searching for his birth parents he kept the image of the tall boy with the belt buckle and the short, round girl in his brain. He looked for years and years to find his parents – and with them his tribe – to no avail.

And for good reason: the students didn’t exist. Cleo made the whole story up, hoping to give her baby some sense of self in a very white landscape.

When my dad finally found his biological father in 2018, he wasn’t a tribal student from the University of Utah. His name was Phil Martinez and he didn’t even know he was Native American.

Now, at the dinner table, we tell the story of how two families with parallel lives found each other six decades later. And with that reunion came new questions on what shapes identity, and how generations of displacement of American Indians affects that identity.

The view from Bear Carrillo’s backyard in Salt Lake City.

Jess Kung/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jess Kung/NPR

The view from Bear Carrillo’s backyard in Salt Lake City.

Jess Kung/NPR

[ad_2]